The principles of active and passive

management

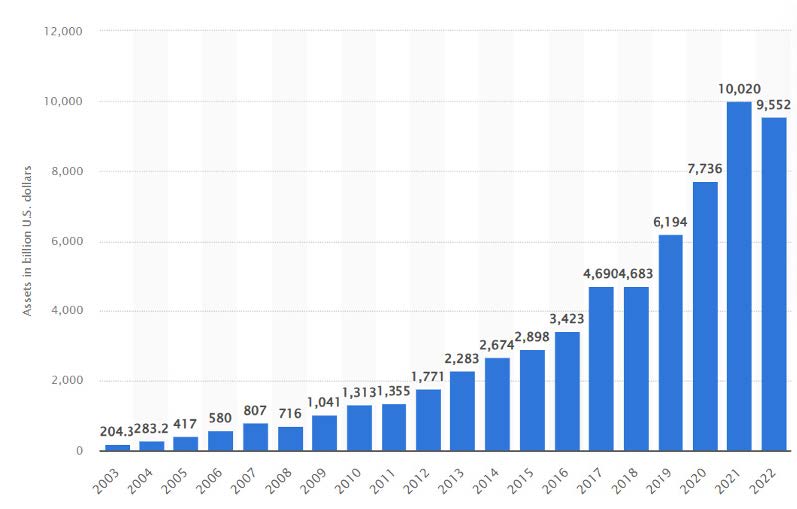

The proliferation of passive management strategies in recent years is well documented by the exponential growth of assets invested in ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds).

Growth in ETF assets under management between 2003 and 2022 (in billions of dollars)

Source: Statista

of an index (e.g., the S&P 500) as closely as possible, generally by buying most or all the securities with the same weighting as the index. The intellectual basis of passive management is the conviction that, over the long term, an active investment strategy cannot outperform the market. This is due to market efficiency and the impact of higher turnover, which increases trading costs and capital gains taxes (in jurisdictions where such taxation exists).

Active management, on the other hand, does not seek to replicate an index, but rather to buy securities with weightings different from those of the index, with the aim of outperforming the index or a benchmark.

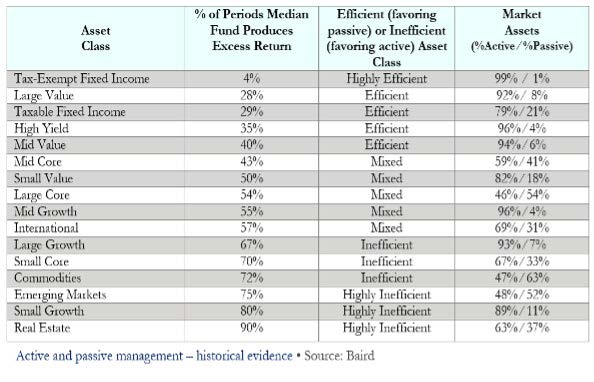

The intellectual foundation of active management is the belief that the market is inefficient, and that those skilled in stock or sector selection can add value through their management, enabling them to outperform a benchmark such as the S&P 500. As the table below shows, both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. Passive management replicates the performance of a market but offers no potential for outperforming the benchmark (or protecting against downside). Active management offers the possibility of outperforming the market but carries the risk that the manager may fail to beat (or even significantly underperform) the benchmark index.

Active and passive management - advantages and disadvantages

Empirical research

Starting from the conclusion that both active and passive management are strategies with their own merits, the question is where and when one is more appropriate than the other. At the end of 2009, Baird & Co carried out an interesting study. It examined several major asset classes to determine which are best suited to active management, and which to passive management. To do this, they measured how often the median mutual fund in a given asset class was able to outperform its benchmark (see the second column of the table below). In the third column, they defined the degree of efficiency of each asset class. Market efficiency is the ability of asset prices to reflect all available information.

As the table below shows, the probability of success of active management depends on the degree of efficiency of a market. In efficient markets, such as US large-cap value equities or bond management, the percentage of periods during which the median fund outperforms is fairly low. On the other hand, less efficient markets, such as emerging markets or US small caps, offer a high probability of outperformance for active managers.

Baird's study led them to ask whether the financial world takes into account the fact that some asset classes are more efficient than others, and therefore whether there is a distinct bias in favor of active or passive management. One way of measuring this assumption has been to determine what percentage of an asset class’s assets under management is invested in active or passive managers (see column 4 of the table above).

Surprisingly, some of the most efficient markets are dominated by active management, for example, US large and mid-caps value equities, both with over 90% active managers, while many of the least efficient markets are heavily invested via passive management, for example, emerging markets and commodities, both with over 50% passive assets. And even if these statistics are relatively old, we must admit that this imbalance is more or less the same at the start of this decade. This position flies in the face of logic and leads us to the conclusion that many diversified portfolios are not optimally constructed.

.png)