What is the debt ceiling?

Set by Congress, the debt ceiling is the maximum amount the federal government can borrow to finance the obligations that elected officials and presidents have already approved.

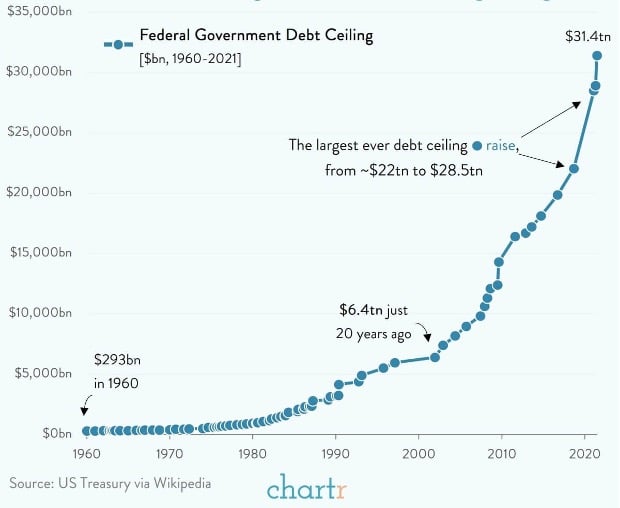

The ceiling, which currently stands at $31.4 trillion, was created over a century ago. Since 1960, Congress has raised or extended the debt ceiling 78 times, including 29 times under Democratic presidents and 49 times under Republican presidents.

A history of the US debt ceiling since 1960

Source: chartr

Source: chartr

Prior to 1917, Congress authorized the issuance of individual bonds to supplement tax revenues to finance specific expenditures. But after World War I, Congress authorized the U.S. Treasury to issue bonds as it saw fit, although it was limited by a debt ceiling. The legislative branch thus ceased to micromanage the issuance of Treasury bonds that finance spending (leaving that function to the executive branch) but retained its authority to ensure the distribution of powers by limiting the total amount of debt issuance, and must still authorize federal spending (source: Lyn Alden).

Raising the debt ceiling itself does not authorize new spending; it simply allows the government to continue to pay its previously authorized spending obligations. Not raising the debt ceiling means that the government must either: 1) not pay previously authorized spending obligations or; 2) default on its national debt, which has accumulated over time.

In other words, the idea of a budget constraint is relevant when deciding new spending and tax plans, but it is not relevant in debt ceiling disputes over past spending plans.

Although originally designed to facilitate federal government borrowing, the ceiling has become a means for Congress to limit the growth of borrowing, making it a fiscal policy issue for the past few decades.

.png)