Introduction

After months of escalating tensions, on 3 January, the United States carried out a large-scale operation in Venezuela, extracting President Nicolás Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores. President Donald Trump confirmed the move, stating that Washington would run the country until a transition could be put in place. The operation marks the first time in more than three decades that the US has seized a sitting Latin American head of state.

Maduro, who has been indicted in a federal court in New York on charges including narco-terrorism conspiracy, has long been a central figure in US sanctions policy and regional pressure campaigns. His sudden removal carries implications beyond Venezuela’s borders, as the country sits atop the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Why did the US capture Maduro?

Nicolás Maduro rose through the ranks of Venezuelan politics under socialist Hugo Chávez and took over the presidency in 2013. Since then, his rule has been heavily criticised, both at home and abroad. Opponents accuse him of persecuting political rivals, restricting liberties, and holding elections that lacked credibility.

Tensions with Washington escalated under the Trump administration, as U.S. officials linked Maduro’s government to drug trafficking and rising migration flows. Pressure intensified in August, when the U.S. placed a $50 million bounty on Maduro and launched strikes against suspected drug-smuggling vessels in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific.

The US alleges that Venezuelan authorities were involved in state-backed drug trafficking, including ties to the Cartel of the Suns, designated as a terrorist organization. Maduro has denied the charges, arguing that US operations were designed to force regime change and take control of Venezuela’s oil reserves.

Maduro’s last public appearance as president came only hours before his arrest, when he met Chinese special envoy Qiu Xiaoqi at the Miraflores Palace to discuss bilateral relations. The meeting suggested that Caracas still viewed its foreign partnerships as a source of political support. Shortly afterward, explosions were heard across Caracas.

This was more than a localised arrest; it was a strategic signal directed at China and Iran. It dismantled the assumption that the US lacked the resolve to act against regimes propped up by foreign adversaries.

Drill, baby, drill

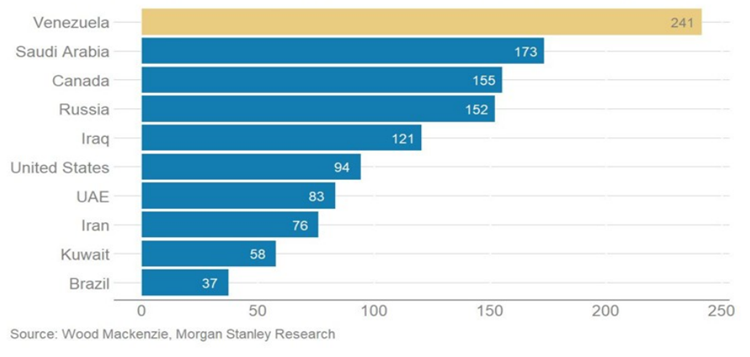

Securing energy resources appears to be a central consideration behind US actions in Venezuela. The country holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves and, according to Wood Mackenzie, has roughly 241 billion barrels of recoverable crude.

Proven Oil Reserves by Country (Billion Barrels)

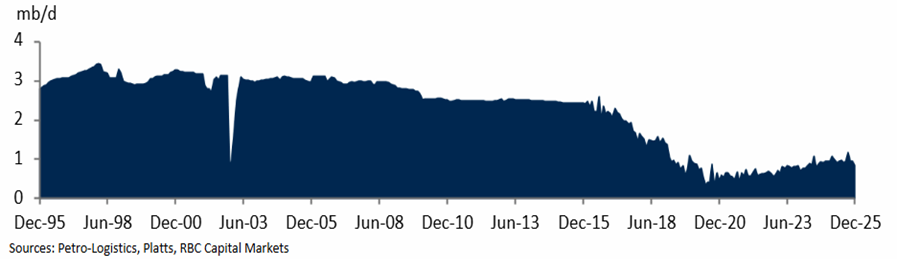

Yet Venezuela’s production history highlights how difficult those barrels are to unlock. Output peaked near 3 million bbl/d in the late 1990s, before political upheaval, strikes, and sector restructuring under Hugo Chávez triggered a long decline. US sanctions imposed from 2017 onward accelerated the collapse, pushing production below 500,000 bbl/d by 2020. Limited sanctions relief in recent years supported a modest rebound, but output today remains around 800,000–900,000 bbl/d.

Historical Total Venezuelan Supply

Expectations of a rapid supply surge risk overstating what is feasible. Iraq took nearly a decade and more than $200 billion to return to pre-war production levels, while Libya has yet to regain its 2010 peak.

Venezuela faces even steeper constraints. Its reserves are dominated by extra-heavy crude, requiring upgrading and imported diluents for transport. Years of underinvestment, sanctions, loss of skilled labour, and the decline of state oil company PDVSA have taken a heavy toll. Aging infrastructure, repeated refinery outages, and limited access to modern drilling and upgrading technology continue to constrain any rapid recovery.

PDVSA has indicated that facilities were not damaged during recent events, suggesting limited immediate disruption. In the near term, oil markets appear able to absorb uncertainty. Inventories are adequate, and OPEC+ has signalled that its 1.65 million bbl/d of voluntary cuts could be reversed if needed.

A pro-US government could enable sanctions relief, renewed foreign investment, and a gradual recovery in exports. However, returning to 3 million bbl/d or more would take years and substantial infrastructure investment. President Trump has already indicated that US oil companies would help operate and develop the Venezuelan oil sector.

Oil markets are tightening structurally. Global consumption now exceeds 101 million bbl/d, led by the United States, China, and rapidly growing demand in India. From a market perspective, the near-term effect may be a temporary rise in geopolitical risk premia. Over time, sidelined Venezuelan supply, close to 1 million bbl/d, could weigh on oil prices and support risk assets.

Source: The Coastal Journal

Source: The Coastal Journal

Venezuela’s resource base extends beyond oil, with deposits of iron ore, bauxite, gold, and nickel, as well as copper, zinc, and rare earth elements, mainly located in the Guayana Shield in the south of the country. Venezuela holds Latin America’s largest gold reserves. Official surveys point to potential scale in battery metals. The government claims reserves of up to 340 million tonnes of nickel alongside large copper resources. Despite this geological potential, commercial mining activity remains minimal. Most non-oil minerals account for less than 1% of national output, and large-scale foreign mining investment is largely absent, leaving much of the country’s mineral wealth undeveloped.

The economic warfare between US and China

Modern empires competition today is less about direct conflict than about control of inputs. Energy, metals, and critical materials function as the grain of the modern world. When leaders signal a willingness to secure those inputs directly, markets should read it not as rhetoric, but as resource strategy.

The US-China rivalry is fundamentally structural rather than ideological. The United States is energy-rich but dependent on imported metals and rare earths. China dominates metals processing but relies heavily on imported oil, sourcing roughly 70% of its crude abroad. Each is strong where the other is vulnerable, and both are seeking to weaponise that asymmetry.

Control over energy flows also has monetary implications. Influence over Venezuelan oil is not only about supply but about reinforcing the Petrodollar and preventing the rise of the Petroyuan.

There is also a regional dimension. China has steadily expanded its footprint in Latin America through infrastructure investment and commodity financing. Recent US actions suggest a push to reassert influence in the Western Hemisphere, forcing Beijing to compete under less favourable conditions. The Trump administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy identified the Western Hemisphere as a core priority, reviving the logic of the Monroe Doctrine, now known as the "Donroe Doctrine". The objective is to place the region’s strategic natural resources, particularly critical minerals and rare earths, under US-aligned corporate control, while building a Western Hemisphere supply chain that reduces reliance on China.

Indeed, much of South America is moving closer to Washington, leaving Brazil increasingly isolated. This matters because President Lula is a self-declared leftist who has consistently leaned toward Russia, China, and Iran. After Trump’s capture of Maduro, Kalshi odds show a 90% chance that Colombia and Peru’s presidents are "out” before 2027. In parallel, President Trump recently reiterated that Greenland should become part of the United States, underscoring a broader strategy focused on securing critical assets.

Source: Kalshi

Source: Kalshi

Which assets could benefit from “nation building” in Venezuela?

A political transition in Venezuela would primarily affect assets linked to debt restructuring, energy infrastructure, and oil supply chains.

Venezuelan bonds currently trade around 25–35 cents on the dollar, reflecting sanctions risk and legal uncertainty. In a regime-change scenario, several analysts estimate recovery values in the 30–55 cent range, driven by restructuring and sanctions relief.

Source: Bloomberg

Ashmore remains one of the largest institutional holders of Venezuelan sovereign debt. Advisory firms such as Houlihan Lokey, financial advisor to the Venezuela Creditor Committee, and Lazard, a long-standing leader in sovereign restructurings (Greece, Ukraine), would likely benefit from the scale and complexity of any restructuring. In such cases, advisors earn success fees and act as “picks and shovels” to the process. Venezuela’s debt stack is widely viewed as among the most complex on record.

Restarting Venezuela’s oil sector would require rapid rehabilitation of ageing assets. Technip, the historical architect of much of Venezuela’s critical oil infrastructure, is well positioned given its proprietary knowledge, particularly if no-bid or sole-source contracts are used to accelerate repairs. Graham Corporation, which supplies vacuum ejector systems used in heavy-oil upgrading and refining, could also benefit, as processing Venezuela’s crude requires vacuum distillation to prevent it from turning into solid coke.

Before exports can scale, Venezuela must import large volumes of diluent (naphtha or natural gasoline) to move heavy crude through pipelines. Targa Resources, which operates the Galena Park Marine Terminal in Houston, a key LPG and naphtha export hub, would be a logical beneficiary if Venezuela shifts back toward US diluent supply, displacing Iranian flows.

The most obvious beneficiary of regime change and nation building in Venezuela is Chevron. Unlike other US majors that left, Chevron has maintained a presence in Venezuela. They have the staff, the licenses (via OFAC), and the fields (Petroboscan, Petropiar) ready to ramp up immediately. Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips, both of which have legacy claims and arbitration awards tied to past expropriations, could regain access or seek compensation under a new framework.

US Gulf Coast refiners, including Valero Energy, Phillips 66, and Marathon Petroleum, were specifically built to process heavy, sour crude like Venezuela’s. Since sanctions, these refiners have relied on more expensive alternative feedstocks. A return of Venezuelan barrels would lower input costs and support margins, assuming stable product demand.

From a sector perspective, oil flooding out from Venezuela would be bearish oil and thus bullish consumer stocks. Lower oil prices is deflationary and could imply lower bond yields, which is bullish risk assets all else being equal.

Note: This section is for analytical purposes only and does not constitute investment advice.

What’s next for Venezuela?

In a typically Trumpian style, President Trump initially said the United States would “run” Venezuela during the transition. US officials confirmed that roughly 15,000 troops would remain positioned in the Caribbean, with further intervention left on the table should Venezuela’s interim leadership fail to meet Washington’s conditions.

Venezuela’s Supreme Court has appointed Vice President Delcy Rodríguez as interim president. Rodríguez, who has served as Maduro’s deputy since 2018, oversaw much of the country’s oil-dependent economy and its intelligence apparatus and sits firmly within the existing power structure. She offered “to collaborate” with the Trump administration in what could be a seismic shift in relations between the adversary governments.

Independent observers, including the UN and the Carter Center, concluded that Venezuela’s 2024 elections lacked credibility and failed to meet international standards. Verified tally sheets reviewed by independent analysts showed opposition candidate Edmundo González winning roughly 67% of the vote, compared with about 30% for Maduro.

At the same time, Nobel Peace Prize winner and Venezuelan opposition leader, María Corina Machado, is projected to return to the country this month, and has stated that the opposition is prepared to assume power. However, President Trump has publicly questioned the extent of her support among the Venezuelan population.

Against this backdrop, three scenarios appear plausible (as outlined by Gavekal Research):

- The "soft" military dictatorship:

The most likely outcome in the near term is the preservation of the existing power structure under Rodríguez and the military. Survival would require a pragmatic pivot toward US interests, including a more business-friendly stance and a distancing from traditional allies such as Russia, China, and Iran. Washington may tolerate this outcome if it delivers stability and access to energy flows.

- Transition to democracy:

A negotiated transition to civilian rule would depend heavily on the design of new elections. Including the Venezuelan diaspora could alter the outcome, while limiting participation to domestic voters may favour remnants of the current regime.

- "Libya Redux" (state collapse):

The most dangerous scenario would involve a breakdown of central authority, leading to military infighting and the expansion of armed groups. Such an outcome would risk civil conflict, renewed migration flows, and sharp disruptions to oil markets.

As of today, the situation remains in a "tense calm." Despite President Trump’s remarks, effective control lies with the interim leadership and the military.

Disclaimer

This marketing document has been issued by Bank Syz Ltd. It is not intended for distribution to, publication, provision or use by individuals or legal entities that are citizens of or reside in a state, country or jurisdiction in which applicable laws and regulations prohibit its distribution, publication, provision or use. It is not directed to any person or entity to whom it would be illegal to send such marketing material. This document is intended for informational purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation for the subscription, purchase, sale or safekeeping of any security or financial instrument or for the engagement in any other transaction, as the provision of any investment advice or service, or as a contractual document. Nothing in this document constitutes an investment, legal, tax or accounting advice or a representation that any investment or strategy is suitable or appropriate for an investor's particular and individual circumstances, nor does it constitute a personalized investment advice for any investor. This document reflects the information, opinions and comments of Bank Syz Ltd. as of the date of its publication, which are subject to change without notice. The opinions and comments of the authors in this document reflect their current views and may not coincide with those of other Syz Group entities or third parties, which may have reached different conclusions. The market valuations, terms and calculations contained herein are estimates only. The information provided comes from sources deemed reliable, but Bank Syz Ltd. does not guarantee its completeness, accuracy, reliability and actuality. Past performance gives no indication of nor guarantees current or future results. Bank Syz Ltd. accepts no liability for any loss arising from the use of this document.

Related Articles

The iShares Expanded Tech-Software ETF (IGV), treated as the benchmark for the sector, has slid almost 30% from its September peak, a sharp reversal for what was considered one of the market’s safest growth franchises. Every technological cycle produces its moment of doubt. For software, that moment may be now.

Nuclear power is getting a second life, but not in the form most people imagine. Instead of massive concrete giants, the future may come from compact reactors built in factories and shipped like industrial equipment. As global energy demand surges and grids strain under new pressures, small modular reactors are suddenly at the centre of the conversation.

Cosmo Pharmaceuticals’ successful Phase III trials in male hair loss has drawn attention to a market long seen as cosmetic. Growing demand for effective treatments has accelerated research and encouraged the rise of biotechnology companies exploring new approaches.

.png)